His father bought him a set of tefillin for his bar mitzvah, of course, and he never missed a day. Many years went by, but the tefillin were never accompanied by a Tallis.

Sometimes he would look around shul and realize he was the only man living independently still without a tallis. When that wasn’t the case – when there would be older men, even seniors who were clearly single – it didn’t make him feel any better. He only felt sorry for them, wondered if they felt pain anymore, and dreaded the increasing likelihood of finding out for himself. When well-meaning fools assured him that “everyone gets married”, he thought of those men. They were surely told the same thing decades earlier.

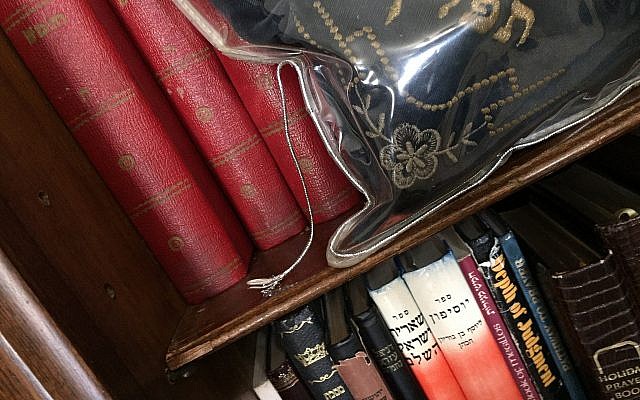

At some point in his 30s, the outer plastic tefillin bag started to come apart. It always happens the same way, every five to seven years on average. First the silver trim around the bag comes loose. Eventually it starts to dangle, and then it comes off completely. After that the edges of the plastic nick and fray, then they tear, and it’s only a matter of time until the bag is tattered, ugly, and useless. The deterioration of the plastic bag can take several months, but once it starts, the end is inevitable.

He waited as long as he could, but it became shameful to continue bringing his tefillin inside the plastic bag. It wasn’t holy like the fabric bag that housed the tefillin directly, so he was allowed to throw it in the garbage, but he still felt bad doing it. The plastic bag was part of his morning shul-going for years, and it deserved a better fate than the greasy aluminum foil from dinner.

He went to shul the next morning cradling his tefillin in just the fabric bag. This presented a logistical problem; the little mirror he used to position the tefillin on his head was not allowed to be placed inside the fabric bag, only the outer plastic one. He carried the mirror in his pocket.

This went on for several weeks, but it was a cumbersome solution. Sometimes, he forgot the mirror at home, since it had to be carried separately. Sometimes he forgot to remove the mirror from his pocket after returning home from shul, and wound up carrying it with him all day. Eventually the mirror fell and broke, and he functioned without one of those as well for some time.

The only real solution was to buy a new plastic tefillin bag. It wasn’t a big deal, but he procrastinated. And he knew why.

He was hoping he would get married in all this time. If he did, the fabric tefillin bag would share a larger plastic bag with a tallis; there would be no need for a smaller plastic bag for the Tefillin. Buying a new plastic tefillin bag was a silent declaration that he didn’t expect to get married anytime soon. He couldn’t bring himself to do it.

A year went by. He really needed a mirror. It took longer to position the tefillin without one, and this wasn’t ideal. He was also tired of the daily morning reminder of his bachelorhood and the little wrestling match over not having a plastic bag for his tefillin. He’d waited long enough, he gave it enough time. He shouldn’t continue to be inconvenienced in this way just because he was single and hoping to get married soon.

Even though he’d made his decision, and it was the right decision, it was depressing to enter the Judaica store and ask for a plastic tefillin bag. It felt final, as if he were investing in extended bachelorhood, resigning himself to remaining single for the entire lifespan of this new bag. It felt as if he were demonstrating that he no longer trusted that Hashem would send him the right one any day, even though it wasn’t like that. He needed a new tefillin bag, plain and simple.

The cost was 10 shekels, about three dollars. He hated having to pay this small amount of money – not because he was stingy, but because he was buying something that was useful only to a single man, something that very few men his age had owned in many years. He wondered if the cashier realized what a quiet tragedy was taking place as he handed over the small coin and took possession of the tefillin bag.

It was nice having one again. It was easier to carry his tefillin, he had room for a mirror, and he considered himself foolish for going so long without one. What had he accomplished? What point did he make? He’d inconvenienced himself all this time for nothing, and might as well have bought the bag long ago.

More years went by. The bag served him well.

One day he noticed the silver trim coming apart just a little. In the course of his life this was a most trivial development, yet it horrified him. Would he have to buy yet another tefillin bag?

Indeed, he would. Several months later the bag was no longer usable. He didn’t wait long this time. He went back to the same store and took a new bag to the counter.

“There’s a special,” the cashier told him. “Three bags for 20 shekels.”

He was taken aback and momentarily speechless. “I only need one,” he finally managed.

“Chaval,” said the cashier. What a shame. “You might as well take two more and save them for the next bar mitzvah.”

He realized this was a thoughtless, tactless comment, but he didn’t pounce on it. His mind was busy calculating. One new tefillin bag would take him close to his 50s already. After two more, he probably wouldn’t be able to be a father anymore, even in the unlikely case that he found someone much younger to marry at that point. Three tefillin bags meant game over, the best-case scenario being that he would find some companionship before he got really old. As it was, he could forget about having a large family. That was buried with the last tefillin bag.

“I only need one,” he repeated, a little more firmly, perhaps a little too firmly. The cashier gave him an odd look, took the money, and wished him a good day.

Then he went shopping for groceries, so he could make dinner.